© Caledonian Park 2023

Privacy Policy Site by 18aThe Keskidee Centre – Britain’s first dedicated arts centre for the Afro-Carribean community

22nd June 2021

The Keskidee Centre was envisioned by Oscar Abrams, a Guyanese architect and cultural activist, in the 1970’s. A centre providing educational, social and cultural activities for a disadvantaged and primarily West Indian community in the borough of Islington, the Keskidee provided a thriving space for Afro-Carribean arts and theatre to flourish in Islington. This was the first dedicated arts centre in Britain for the black community and would continue to be an important hub for African and Afro-Caribbean politics and arts well into the 1980’s.

In 1948 the British Nationality Act was enacted, conferring British nationality to all citizens within the Commonwealth and Colonies, and enabling them to work and settle in Britain with their families. Britain needed people to help rebuild the country after the Second World War and to assist with labour shortages in the transport system, postal service and the newly formed National Health Service. Many Britons from the former colonies within the West Indies, including Jamaica, Trinidad and Barbados, were invited to come Britain.

Between 1948 and 1970 many thousands left their homes in the West Indies to live and work in Britain. There were a variety of reasons behind this migration. Many people were seeking new opportunities for themselves and their families and were attracted by the prospects in what was frequently referred to as ‘the mother land’. Some were looking to settle permanently in Britain, others to work in Britain for a while, save money and return home. Many were returning soldiers from the West Indies who had fought for Britain during the Second World War.

In 1948 just under 500 people arrived from the West Indies. This number rose significantly year-on-year, and by 1972 300,000 West Indians had settled permanently in the United Kingdom. This wave of arrivals has been labelled the Windrush Generation, referencing the ship MV Windrush which carried the first Caribbean workers to Britain in 1948. These migrants were not always warmly welcomed by Britons and were frequently discriminated against. Black Britons often found it hard to secure housing and find employment, despite a national shortage of workers. Available housing tended to be low quality and found in poorer inner-city areas.

Throughout the 1950s right wing parties and politicians such as Sir Oswald Mosely, the former leader of the British Union of Fascists, exploited the growing resentment against black Britons. The summer of 1958 saw an increase of violent attacks against Black people, culminating in riots in Notting Hill, which had a large Caribbean community, as well as the city of Nottingham. In 1959, a Caribbean Carnival was held in Notting Hill in response to the riots and the general mood of race relations in Britain at the time. This event was the precursor to the Notting Hill Carnival which has grown to become Europe’s largest street festival. Bowing to growing public pressure, the British government restricted immigration by enacting the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and by 1972 only people with parents or grandparents born in Britain could permanently reside in Britain, effectively curbing immigration from the West Indies. By 1972, 172,000 people from the Caribbean, an entire generation, had permanently settled in Britain and were contributing across all sectors of society.

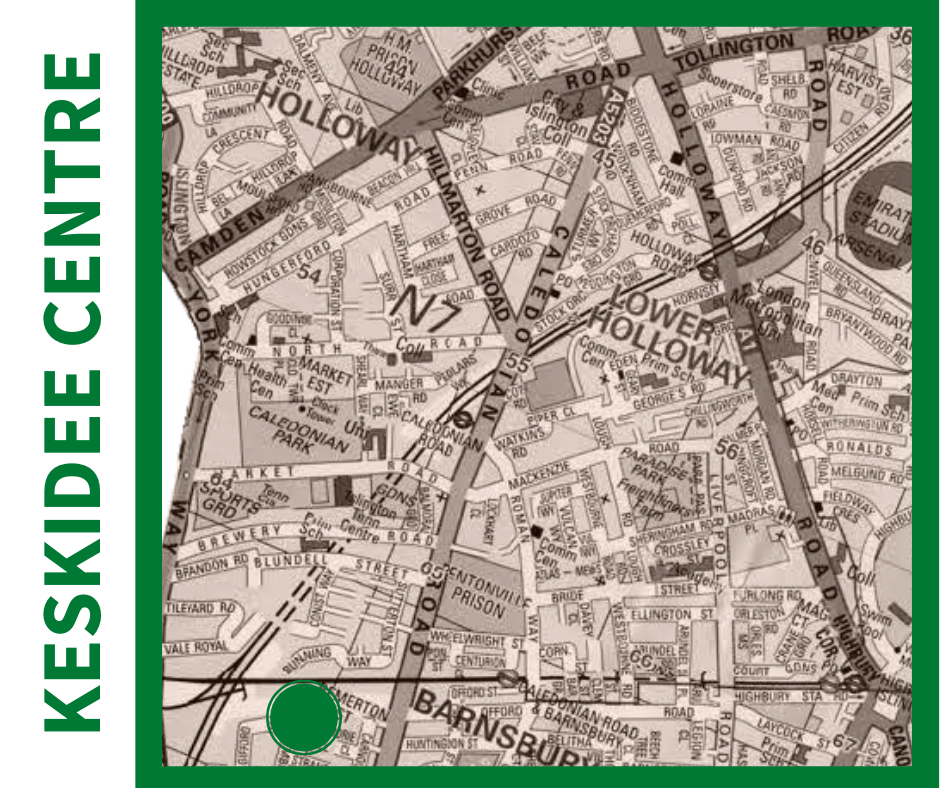

To meet the needs of the growing Caribbean population in London, a community and cultural centre was created. The Keskidee Centre project was the vision of Guyanese-born architect and cultural activist Oscar Winston Abrams (1937 – 1996). Abrams arrived in Britain in 1958, later becoming Chair of the Islington branch of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, which fought for better housing and education for newly arrived black Britons. Abrams wanted to provide both self-help and cultural activities for the local West Indian community under one roof.

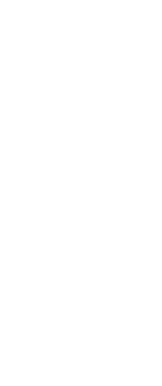

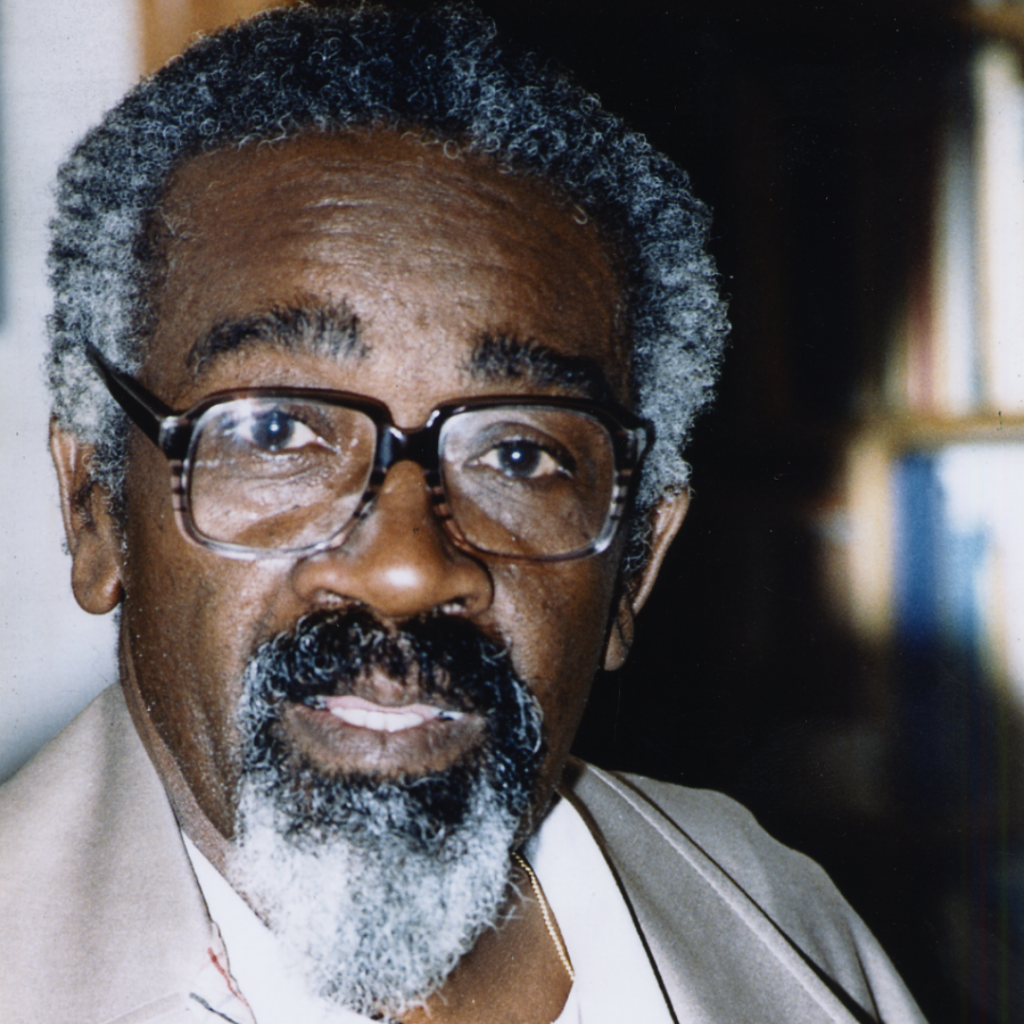

In 1971, Abrams bought the former Gifford Mission Hall on Gifford Street, close to Caledonian Park, for £9,000. Later that year it was formally recognised as the Keskidee Centre, named after a bird native to Abram’s homeland. The centre was to provide a unique and hugely influential cultural and political environment throughout the 1970’s and the early 1980’s. The Centre’s motto was ‘A community discovering itself creates its own future.’

The Keskidee quickly became a thriving cultural venue and, for many years, it was the only place to experience Caribbean theatre in London. The centre also offered legal advice and practical classes on literacy and typing, yoga and cookery, as well as photography, painting and pottery. During the building’s early days, the location proved a drawback. Many people unable to find it. Additionally, actor and director Yvonne Brewster remembers, “there was the train line that ran behind it. So during performances sometimes you had incredible competition from iron wheels.” Oscar Abrams said he was “full of joy” when the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM), which wanted to increase the recognition of West Indian art forms within British society, approached him to use the Keskidee for its own events. He knew John La Rose, one of CAM’s founder members, and strongly believed that the centre would be enriched by hosting the movement’s activities.

Music, art and poetry all played a vital role in attracting young black people to the centre. African and reggae roots music found a spiritual home at the building and provided many young black people with their first experience of live music. Up and coming bands such as Misty in Roots and Steel Pulse played to an eager audience and in 1978, world famous Jamaican musician Bob Marley used the centre to make a video for his song Is This Love? featuring a a young Naomi Campbell who took part along with other children. The Centre also held regular dances and discos.

The Keskidee Theatre Workshop was a full-time pioneering drama company totally dedicated to black theatre. Directors such as Rufus Collins and Howard Johnson, playwrights Lennox Lewis, Derek Walcott and Edgar White, and actors like Yvonne Brewster, Anton Phillips and T-Bone Wilson all contributed to the centre’s creative process. Backstage technicians were selected from the black community, including one of the Caribbean’s leading theatre designers, Henry Muttoo. Equally ground-breaking was the Keskidee Community Theatre Workshops, which concentrated on developing work directly influenced by the experiences of the black community within contemporary Britain.

Linton Kwesi Johnson, who created dub poetry at the Keskidee, was also its first paid library resources and education officer. His poem Voices of the living and the dead was staged at the centre and produced by Jamaican novelist Lindsay Barrett, with music by Rasta Love reggae group, “it was fantastic, you know, having written something and having it staged with actors and musicians. That was back in 1973 before I had a poem published anywhere. That was before anyone had ever heard of Linton Kwesi Johnson.”

The Keskidee addressed the needs of local youth and gave a generation of black teenagers a space of their own. Abrams wrote, “…teenagers respond drastically to anything they call their own. The Keskidee Centre aims to be their place.” This was echoed by a Keskidee youth who experienced life at the centre during the 1970s, “for this area I think it was good, you know, not just the centre but as a young black guy growing up because when you’re young you ain’t got a lot of self-direction. It helped me to grow anyway.”

The centre also provided a forum for political discussion. It facilitated speakers from Grenada, Uganda and Zimbabwe, who often lectured about colonialism, national liberation and the evils of imperialism. Linton Kwesi Johnson remembers the leaders of the main political gangs in Jamaica coming to meet Bob Marley at the Keskidee to persuade him to go back to Jamaica to perform at a peace concert.

By the late-1970s, the Keskidee’s reputation reached distant shores, resulting in theatre tours of Europe and the cross-cultural Keskidee Aroha tour of New Zealand in 1979, where the company met and performed to remote Maori communities. During this period, the Keskidee Theatre Workshop was also selected to represent Britain at the New York Lincoln Center Fringe Festival. These overseas tours were a timely reminder of just how far the Keskidee had come in its short existence.

The Keskidee Centre reached its peak in the mid-1970s, but by the early-1980 it had fallen into decay. Diminishing funding and the pressure of combining so many activities under one roof led to crippling debts and, consequently, its demise; the costly 1979 tour of New Zealand was later identified by Abrams as the origin of the centre’s financial difficulties. By the late-1980s, the centre attempted to reinvent itself as a theatre crafts training centre for black youths; However, by 1992, the venture had proven to have only a marginal reach and closed. The property subsequently sold off.

The former mission hall came full circle and reverted back to religious use, housing the Christ Apostolic Church and the Power-Age Christian College. A green heritage plaque was unveiled at the church on the fortieth anniversary of the opening of the Keskidee Centre by David Lammy MP and former resident artist Emmanel Jegede.

Sadly on 8 March 2012, a devastating fire broke out and ravaged the building, raising it to the ground. The site remains empty today, however its legacy lives on. In 1987 Abrams said, “the most outstanding achievement for me personally is the consciousness the Keskidee brought to the black community and groups that subsequently became interested in the arts.” This remains a fitting epitaph to his, and the Keskidee Centre’s, inspirational legacy and the critical role it played in Britain’s recent social history.

This article was originally produced for Islington as a Place of Refuge, an online tour developed by Islington Museum and Cally Clock Tower, in conjunction with Islington Guided Walks. Centred around Refugee Week 2020’s theme of ‘Imagine’, Islington as a Place of Refuge explores diverse stories from migrant history in relation to the London Borough of Islington.